The student-led RHS club No Place for Hate has come a long way from its origins as a focused response to antisemitism at the high school level.

In early November of 2021, RHS faced a distressing surge of antisemitic incidents, including students openly displaying Nazi imagery like swastikas. Promptly, both the Rhinebeck administration and the Student Council released statements unequivocally condemning these acts and affirming a zero-tolerance policy for all forms of hate within the school community.

At the time Principal Davenport aptly noted, “the expressions of hatred and intolerance are the result of a lack of understanding, not of malice.” Similarly, the Student Council expressed a desire “to further educate our community on this important topic.”

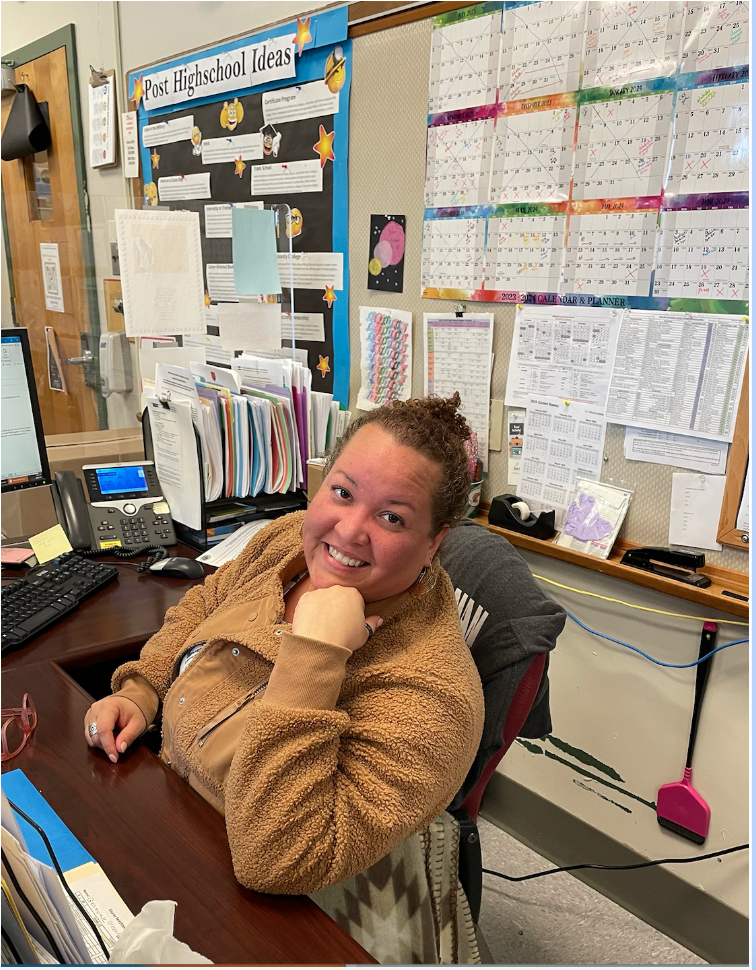

From this educational necessity emerged No Place for Hate, a club dedicated to student education and championing “understanding, acceptance, and compassion towards other people and students,” as described by club advisor Henry Frischknecht.

Beginning with educational presentations in English classes, No Place for Hate expanded its initiatives to include pledge signings and school-wide assemblies focusing on the Holocaust, featuring guest speakers sharing their experiences. According to club President Laila Alam, No Place for Hate has evolved significantly, steadfastly committed to the ethos of “promoting positivity.”

However, there remains a considerable uphill battle in educating the broader student body about the true purpose of No Place for Hate. Feedback from freshman attendees of the club’s recent successful Multicultural Extravaganza, where students were exposed to diverse cultures through food, presentations, and various media, revealed considerable confusion about the club’s purpose.

In talking with multiple freshmen in the lunchroom, every one of them expressed a general lack of knowledge about what exactly No Place for Hate does. Many freshmen also expressed a desire to change the name “No Place for Hate” to something that reflects a more positive message of cultural unity.

Freshman Sophia Santoro articulated this sentiment, stating, “It feels like [with the current name] you would be talking about not bullying instead of sharing cultures which is what the multicultural festival was all about.”

Similarly, freshman Kate Reichelt emphasized that “The event was about the culture of food; it wasn’t saying don’t hate on people.”

In talking with faculty advisor Mr. Frischknecht, he admitted that marketing the club and getting its message out there is “something we need to do a better job of.” He also agreed that the club’s name should be reconsidered but that any name change would likely be a district decision.

Frischknecht explained the origins of the name “No Place for Hate,” tracing it back to the club’s initial intention to align with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization primarily dedicated to combating antisemitism. The ADL’s website boasts a network of over 1,600 schools nationwide with similar “No Place For Hate” clubs, emphasizing the collective responsibility to combat bias and bullying.

Initially, the club aimed to be directly tied with the ADL, but it soon became apparent that ultimately club members were best suited to determine what was best for Rhinebeck. And while Mr. Frischknecht occasionally consults the dense ADL handbook and guide for No Place for Hate Clubs, attempts to engage with the organization have gone unanswered.

Looking to the future, club president and graduating Senior Laila Alam expressed optimism and hope for No Place for Hate’s trajectory and outlined her plans for future leaders.

“We would have a concrete list of events that cycle on a four-year basis. Students in the committee could choose from a list of prior events that have had success based on issues they’ve witnessed in our school community or activism passions”

Mr. Frischknecht aims to enhance these events by incorporating expert speakers to address various forms of hatred and raise awareness of minority groups. However, he acknowledges the challenges of addressing complex issues beyond antisemitism.

“It’s more difficult to bring a speaker in that wants to talk about the ongoing Israel-Gaza conflict or LGBTQ+ rights and advocacy,” Frishknecht noted.

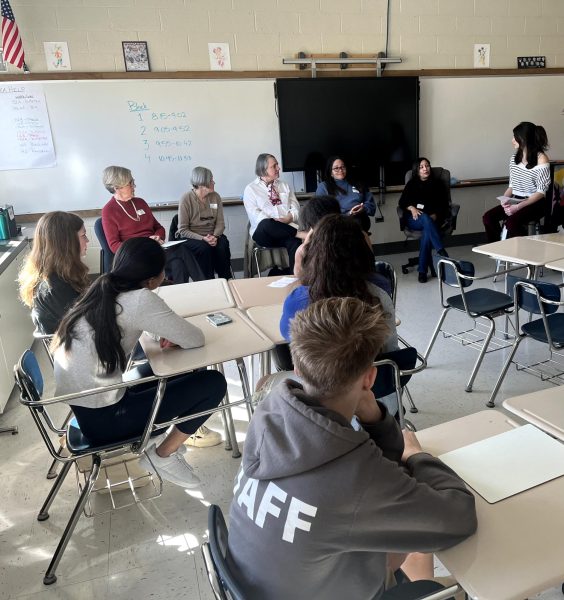

But both Alam and Frischknecht are up to the challenge and have already begun to expand No Place for Hate programming into elementary and middle schools through events centered around exposure to diverse cultures, mirroring the high school’s multicultural festivals. At the middle school level, collaboration with the peer leadership program has allowed for club members to deliver presentations on Bystander Intervention training to sixth graders.

Mr. Frischknecht noted the widespread receptiveness from teachers and students alike to the introduction of No Place for Hate’s core messages of compassion and inclusion into elementary and middle school settings. His vision entails a pathway where students can interact with different branches of No Place for Hate across all three Rhinebeck schools. This approach ensures that students become familiar with the club early on, increasing the likelihood of their participation in leadership roles once they reach the high school level.

When discussing the future of the club, Alam injects optimism, expressing faith in the younger club members such as sophomore Ellie Firestone who will soon be entrusted with its stewardship. She emphasizes that “being in a position like this is so valuable for someone our age; it is empowering.”

As the No Place for Hate club begins a new chapter of promoting inclusivity and diversity, the importance of sharing its efforts and progress with the larger district becomes even more imperative. Effective communication not only builds understanding within the school community but also strengthens the club’s message of acceptance and compassion. Thus, it is not just a matter of necessity but a responsibility to share the meaningful work of the club—a responsibility that empowers curious students to join the organization, sustaining its efforts for years to come.